Aaryn Lang on Being More Than a Muse and Her Grant to Support Black Trans Women Artists

Entertainment

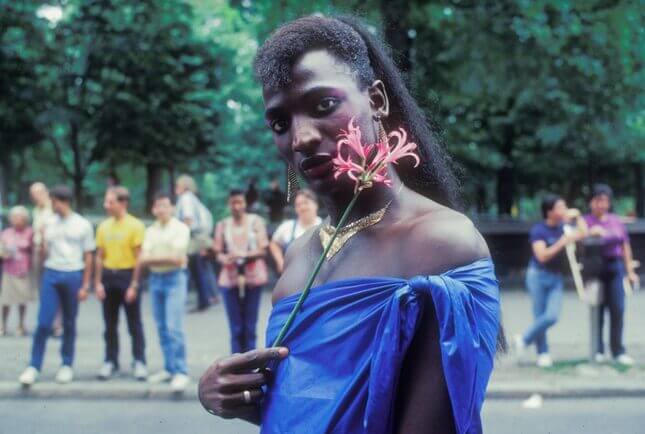

Marsha P. Johnson’s smiling face graced the halls of the Whitney Museum of Art last year as part of an Andy Warhol retrospective. Walking through the exhibition, I instantly recognized the S.T.A.R. revolutionary, color-blocked in the Warhol portrait as per the artist’s distinctive pop art style. Reading more about the portrait, however, I was disappointed if not totally surprised to learn that Warhol never formally named Johnson as the subject of this piece. That connection was made through subsequent research later on.

Though Johnson is basically a household name these days, at least in queer circles—largely thanks to the artist and filmmaker Tourmaline’s archival work concerning Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, and other trans foremothers—Warhol thought nothing of relegating her to the chorus of unnamed trans women and drag queens who sat for his Ladies and Gentlemen series. It’s a common dynamic in the visual arts—the white cis artist capturing the Black transfeminine muse—and it’s one that Aaryn Lang says needs to change immediately.

“We’ve got to take this back for ourselves,” says Lang, a consultant, writer, and public speaker who lives in New York City. “I think we’ve seen, at this point, that cis people really don’t know how to push the conversation any further than it is now.”

That is why Lang, along with photographer Mariette Pathy Allen and multidisciplinary artist Serena Jara, spent the past year and a half developing the Illuminations Grant for Black Trans Women Visual Artists, administered by New York City-based LGBTQ+ arts organization Queer|Art and the New York Community Trust. The newly established annual grant, announced last week, will award $10,000 to a Black trans woman or trans femme visual artist at any stage in her career. The recipient will be selected by a monumentally impressive judging panel—The Studio Museum in Harlem director and chief curator Thelma Golden; poet, performer, DJ, and visual artist Juliana Huxtable; visual narrator Texas Isaiah; and multidisciplinary artist Kiyan Williams—that will rotate every year.

“We need the vision of Black trans people at the forefront to be unfiltered and ‘for us, by us.’ The Illuminations Grant is FUBU at its finest,” Lang adds with a laugh. “It is literally the vision of a Black trans woman for Black trans women.”

I recently had the chance to speak with Lang about the grant and how it came together, as well as the greater question about artists and muses and what she envisions for Black trans women in the art world more broadly. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

HARRON WALKER: When I was reading about the Illuminations Grant, I was struck by the part about how it aims to challenge the art world “to see Black trans women as more than mere subjects” but as artists in their own right. How does that dynamic play out in the art world?

AARYN LANG: The relationship between subject and artist is complicated. Who gets to be the artist? Who gets to document life? Who is allowed to tell stories, and what have the outcomes of that answer been? Wealthy artists get to travel the world and take pictures of people—people who are living full lives, who do not just exist in connection to certain issues but have families and cultures just as expansive as those wealthy artists have. But they get reduced down to whatever agenda or narrative the artist documenting them is trying to build.

Is this a matter of excellence or access?

We don’t just see it with art. We see it in many different industries. People of many crafts use Black trans women as a means to push their agendas, whatever they may be, without actually consulting with Black trans women about what we want. One way that we’ve seen that lately is with the deaths of Black trans women, using them as a kind of mascot for liberation. It’s meant to evoke a kind of feeling for Black trans women, but I fear that what it actually does is reinforce a connection between Black transness and death. What I’m so desperately focused on in my work now is not connecting Black trans women simply to death, and part of that is giving Black trans women the tools to tell their stories, express themselves, and reveal how Black trans women make sense of the world around us.

This grant does that. It creates a pathway to success that doesn’t include having to be a muse for someone else. It’s about making the subject the artist—making the subject the creator. In the art world—everywhere, really—there’s this idea about who Black trans women are. The Illuminations Grant is actually opening the floor up to hear from Black trans women ourselves.

And the name of the grant itself reflects that question of access. From what I read, Queer|Art usually names its grants after established artists—like the Barbara Hammer Grant for lesbian filmmakers. You all decided not to name this grant after anyone in part to reflect the absence of documented Black trans women visual artists in history.

This industry is not welcoming to Black trans women. Even if the spaces don’t outright say that, so many factors around access and resources lead to why we’re not there—and the people in those spaces think that’s OK. There can be a room full of artists looking at photos of Black trans women, feeling moved by those images, but nobody questions why there are no Black trans women in this space. Why is there only one Black trans woman that we know of? Is this a matter of excellence or access? That’s what this grant is about.

People are trying to wax poetic about us, while we are trying to talk for ourselves.

Coming from movement and the nonprofit space, there are many Black trans women. People think that’s because Black trans women always want to be in movement work, but it’s largely due to the funding that goes into that space. The funding goes to nonprofits for Black trans women to come in to combat transphobia or whatever other crusade foundations and funders care to support. We have to survive, so we go where there is an opportunity to sustain ourselves.

I believe in building on that model, so that we can create avenues for people to come in and succeed and potentially shift the conditions of other industries, as well. It’s ambitious, and I’m not naïve enough to think that this grant will put an end to Black trans women being murdered or disproportionately impacted by homelessness. But I want to see what happens to the art industry three or four years from now when we have four new Black trans women visual artists coming in and shaking up that space, providing art we’ve never seen before.

I think of Tourmaline. I think of Juliana Huxtable. I think of the amazing work these women have created and how critical their work has been to all of our psyches. What happens when we get 50 Juliana Huxtables? What happens when we get 50 Tourmalines? What happens to this space when the art world is saturated with Black trans women? That is the question.

What does it mean for Mariette Pathy Allen, a cis artist who has been photographing transfeminine subjects in her work for decades, to have played a crucial role in creating this grant?

I met Mariette a little over a year ago. She and Serena Jara had been working on a grant together since about the end of 2018, and I was brought in the following February to make it make sense [laughs]. Serena and Mariette were looking to create a grant for trans people, and I said, “Make it for Black trans people. Make it for Black trans women.” If that was the intention, then make it more intentional.

Before we began our official working relationship, Serena, who is a friend of mine, convinced Mariette to sit down and consult with me, one-on-one. In those initial conversations, I didn’t just speak about what kind of impact funding like this would have on the industry—I made it clear that this was a way that she could take her career, which one could say is pioneering in its own right, and pioneering in a new way, by directly offering to support the most marginalized people in the community that she has been photographing all this time. For the past 40 years, she has taken pictures of crossdressers, gender-nonconforming folks, and trans folks with the desire to humanize us. I think that’s really noble, and I do applaud that work. But after 40 years, you’d hope that all that humanization would have led us to these industry spaces welcoming the newly humanized with open arms, and I don’t believe we’ve seen that. I challenged Mariette to see outside of herself and to see that her role could be more than just trying to humanize us through photographs. She could facilitate space for us to actually share our own humanity on our own terms.

The girls can do whatever they want.

When we take pictures of people who are marginalized, when we march in the street for people, the idea is not that we do this forever. It’s supposed to be a means to an end. We accept voyeurism as a mode of support. We accept tokenization as a mode of support. We accept that making one individual a kind of magical exception is a mode of support—but what of the broader community, with its wealth of experiences and viewpoints? People are trying to wax poetic about us, while we are trying to talk for ourselves.

I challenged Mariette all throughout this process, and when she finally got it and became a champion, that was probably the most beautiful thing for me to see. Mariette has been really courageous in looking beyond herself.

Who is the ideal candidate to apply? Who do you think would benefit the most from this grant?

This grant is really for any Black trans woman visual artist. Early career artists, artists of all ages, artists who haven’t had an exhibition, artists who have. I want people who are not in coastal cities to have this opportunity. I really, really encourage Southern and Midwestern Black trans women to apply. But honestly, it’s for all the girls. You could’ve been doing this work for 10 years. You could’ve been doing this work for five. If the work is good, if the work is moving, it’s time to apply.

This is a prestigious award, and this judging panel is phenomenal. This is a Black-ass grant [laughs]. It is being judged by a prestigious, talented, and revered panel of Black artists and Black industry professionals, you know? Changemakers, movers, and shakers. That, to me, is a big part of this grant that I hope makes Black trans women want to apply. The judges won’t bring the gaze of whiteness to their work. The eyes that are going to be laid upon their work are going to be Black. They will understand the experience and conditions that this work speaks to and springs out of.

The $10,000 is also totally unrestricted, meaning you can use it however you want and don’t have to perform for it. The work doesn’t have to be about “being trans.” It doesn’t have to be about Pride or connected to a civil rights icon. We’re not requiring anything but the work and talent you already possess. The girls can do whatever they want.

I don’t want this to be something where the girls are second- and triple-guessing themselves. This is an amazing opportunity for all Black trans women who want to break into this field. We’re creating a pathway into the art industry as it’s established. I want everybody to apply. If you’ve got the work to submit, apply.

Learn more about Aaryn Lang and her work on her website, and follow her on Instagram.

Apply for the Illuminations Grant for Black Trans Women Visual Artists here.