Advice for Surviving Lockdown, From a Woman Who Spent Two Years in a Closed Glass Structure

Entertainment

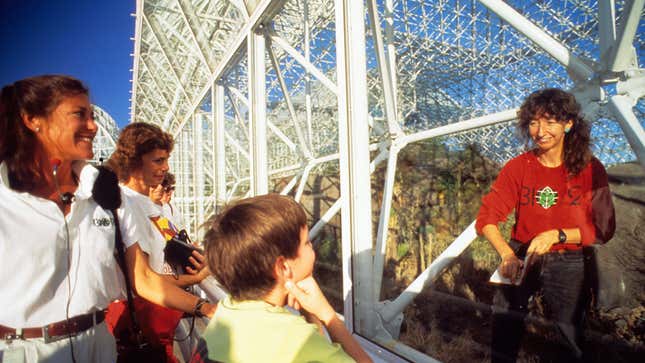

Botanist Linda Leigh was among the eight specialists who spent two years in effective quarantine as part of the notorious Biosphere 2 experiment of the early ’90s. The heavily hyped experiment sought whether life could thrive in a closed system. The so-called “bisopherians” had access to several biomes within the sprawling three-plus acre structure, though interpersonal conflict and a roach infestation made the environment less than idyllic. When outside objects were introduced after the experiment was underway and oxygen was pumped into the structure, the media declared Biosphere 2 a failure.

And yet nearly 30 years later, Leigh rhapsodizes her experience. She does so in Matt Wolf’s new documentary about Biosphere 2, Spaceship Earth, and she did last week to Jezebel via phone. Leigh lives in Arizona, about 10 miles away from the Biosphere 2, which is now owned by the University of Arizona. Her work today involves community gardens and food security issues, and she says that her life hasn’t changed much in lockdown “other than wondering who people are when I see them with a mask on.”

Leigh told me about her experience inside of Biosphere 2, her thoughts on Wolf’s documentary, and the similarities and differences in her experience then and the worldwide lockdowns currently underway. An edited and condensed transcript of our conversation is below.

JEZEBEL: The Biosphere 2 experiment started almost 30 years ago and you’re still talking about it. Were the two years that you spent in there as monumental to your life as your continued discussion of it suggests?

LINDA LEIGH: Yes. It wasn’t just the two years for me. It was the six years of working with a lot of specialists at figuring out how to put a world together. That six years was equally as exciting and thrilling as living inside for two years, believe it or not. I also worked on the Biosphere after the two years. I did a dissertation around some of the work that we had done inside of the Biosphere. So for me, it’s been 15 or 20 years of work, which is a quarter of my life, stretching it. I’m not surprised that I’m still talking about it because it has been a significant chunk of my life.

What do you think of the documentary?

I love the documentary. My jaw dropped when I watched it the first time at Sundance. The beginning part, which takes place in the ’60s and ’70s, I wasn’t involved with, so I learned a lot about the background and it all made a whole lot of sense. He portrayed a lot of the ideas of the Biosphere really well.

Do you feel vindicated by the documentary?

There are still people who are negative about [the experiment], and that’s okay. Is there anything on earth that everybody agrees on? The Biosphere is just another thing. It’s important to have people on both sides, but it’s important that they talk to each other. I think that what Matt [Wolf] and [producer Stacey Reiss] did was they kind of showed the dialogue of the people who didn’t really see it for what it was and the people who advanced the idea of it being a scientific project.

Is there anything on earth that everybody agrees on? The Biosphere is just another thing.

When you were in there, did you have access to the media coverage? Were you aware of what people were saying about the experiment?

Yes, we were. There were lots of people on the outside who were helping to manage the Biosphere, [and they] would come up with newspaper articles and read them to us or show them to us, or call us and say, “There’s more bad news from the media.” You know, we just had to keep on keeping on. We were told by one of our publicity consultants that, “You should weigh your press reviews rather than read them because even the negativity gets people thinking about it.”

When the movie was being put together, no one had any sense that the country would be in lockdown. I know your day-to-day hasn’t changed much, but do you have any sense of deja vu?

You know, it’s an interesting thing. People think it’s similar, and there are similarities in that we couldn’t leave the Biosphere, but you’re talking about a couple of acres of a very beautiful, ecological system on the inside that we were in charge of and could work with. I hear a lot of people saying that they’re bored staying at home, but being inside the Biosphere was never, ever boring. We didn’t have the social media and interaction that we do now. There was a very little amount of pre-email stuff happening and things called bulletin boards. But people would come up to the glass and we would touch hands through the glass. I guess in a sense, not being able to touch people or hug them was the same. But really, if you look at the pictures of the Biosphere, it’s a very large thing that looks out across the very high grassland. It’s a different thing.

I hear a lot of people saying that they’re bored staying at home, but being inside the Biosphere was never, ever boring.

On the other hand, missing certain things, certain cultural things was an important part of our experience. I like going to cafés with friends, so what we did inside of Biosphere 2 was we created our own cafés. You might miss going to a theater production. Well, we did theater with people at the electronic café in Santa Monica back and forth. All we had was this technology called video phone, which would shoot one single image across the telephone using fax technology. We’d send one picture of us playing music inside the Biosphere to the musicians in Santa Monica and they would do the same back to us. It’s kind of similar to what people are doing now when they play music for each other, but it was much slower.

Did you ever experience cabin fever or regrets for signing up to be locked away for two years?

I never had cabin fever. I just loved that world so much. One thing that’s not really cabin fever—maybe it is a little bit—is that I like hiking and you couldn’t really hike far in one direction inside the biosphere. You could go around in circles, but that was about it. I never felt like I had a problem with confinement. I never felt confined. It’s a big space. In fact, it’s a bigger space than most people occupy day-to-day.

Did the experience change you?

Yeah, being inside the Biosphere changed me in a couple of ways. One is there were some rough times there for various reasons. If I look back, I see myself in a pretty negative light. I got to be pretty nasty at times and I didn’t like that person. In retrospect, I can see who that person was and see the challenges that I have in my own personality. It became far more obvious with seven other people. Another thing is communication and the importance of being able to communicate with the people you work with, the people you love, the people you’re surrounded by. We failed at doing that very well, even though we kept working together till the very end of the two years, our communication was not very good. That made a big change. I think the way I look at life systems now is really different. When I look at a tree, I don’t think “tree”—I think oxygen. I think of carbon dioxide. There’s a palpable change in thinking as to how plants function in life.

I miss it. I miss the life of being completely responsible for my whole environment and knowing what’s happening. Knowing that if I dig a sweet potato that I’m going to get a puff of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. What does that mean? It means a whole lot of other things are going to happen. I miss that way of thinking a lot. I miss that lifestyle.

You said your experience differed considerably from what people are experiencing now, but nonetheless, having been through your own self-imposed lockdown, do you have any tips for those who are going through that now?

One thing that can help is to keep a journal. Keep writing down what you’re feeling and what’s happening. People in the city, in apartments, probably have less contact with other people so they’re missing being able to tell people what’s going on in their heads and what’s going on in their lives. Document what’s happening. That helps a lot. Do a lot of outreach with other people, not just listening to music, but active outreach: talking back and forth. Those are two really important things. Also, exercise. I think there might be people who aren’t getting much exercise right now. You can just walk in place, march in place, run in place. Those kinds of things will keep you in a more positive mindset. We know that exercise makes a big difference in possible depression and so forth.

The movie didn’t really go into romance or sexual contact ever occurred in the Biosphere.

Well, [it didn’t] for me, but I can’t really talk for everyone else. There were two couples inside the Biosphere, but what happens behind closed doors is their story.

Do you keep in touch with them?

We had a reunion last November, right here in Oracle, Arizona. I hadn’t spoken with some of the other biospherians since we got out, really, since 1993. There were some not really good feelings between us when we departed. But that all melted away and it was just so wonderful to see everybody. I have a little bit of contact with just about everybody. And I have so much respect for what everybody’s doing in the world now and for what we did then.

When you look back on it all, what do you think are the greatest lessons to extract from the experiment?

No matter what we think is happening in the environment—we put in a certain number of plants and animals and so forth—you’re not going to end up with what you think you’re going to end up with. When we do restorations of ecosystems, even if we put the identical plants in, we’re not going to end up with what we want. In my own field, which is systems ecology, we learned that systems will become systems even though you put them together piece by piece, but it’s going to be a surprise as to what that system is in the end.

Regarding mindsets on climate change, it seemed like in the early ’90s, we flubbed an opportunity to really sort out our future. I wonder if you agree.

There is a reason for hope, as Jane Goodall says. We’ve got to make it so that hope is not just a placeholder for action. “Hope” is saying, “I hope someone else does it.” If we have hope for the future, we must do something about it, because it’s not going to happen without us. I mean, a world will happen without us, but it might not be the kind of world we want to live in. This is what I was saying about systems organizing. You can hope all you want, but unless you act, the hope isn’t going to get us very far.

Spaceship Earth hits drive-ins, “select pop-up city-scape projections (safely accessible by quarantined city dwellers),” and digital outlets today, May 8.