Living Vicariously Through the '90s Teen Beat Bad Boy

Entertainment

Photo: George Rose; John Clifford/New Line Cinema; Albert Ortega/Online USA, Inc.

Recently, roughly a quarter of a century after I fell into an adolescent obsession with Leonardo DiCaprio, I re-watched Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film Romeo + Juliet. What struck me—aside from the fact that I still had most of the script memorized by heart, and that I still found it near impossible to watch without reciting it—was the realization that the scenes I cherished most as an adolescent were not what you might expect. Yes, I loved the elevator kiss and the pool kiss and the balcony kiss. But those scenes were not quite so moving as when a banished Romeo learns of Juliet’s—SPOILER ALERT—“death” and drops to his knees to scream to the heavens with clenched fists.

I obsessed over quieter moments of brooding—say, Leo writing poetry in a notebook with a cigarette dangling from his lip. But I was especially drawn to displays of great, big, raw emotion. Grief, rage, horror.

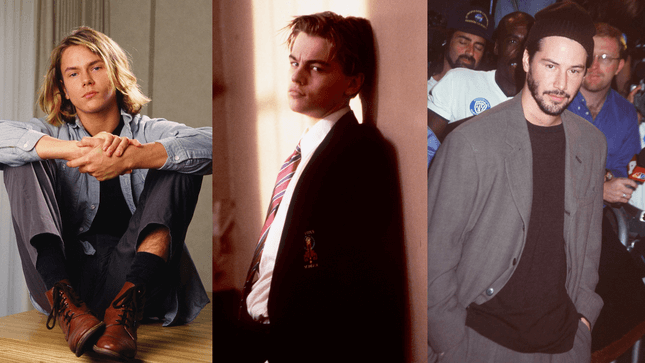

Part of his appeal as the sensitive, troubled bad boy was his ability to feel and express. I was a teen girl hemmed in by social expectations around feminine pleasing and containment—but I could live vicariously through the emotions and actions of my angsty pretty-boy avatar. I was in good company, and so was the angsty pretty-boy avatar. The archetype proliferated in the ’90s, from the dreamily tender River Phoenix in My Own Private Idaho to Luke Perry’s tough-but-kind Dylan on 90210. This brooding man uniquely reflected the loosening of masculine expectations, and straight women’s fraught desires, in a time of contradictory social progress.

Of course, the bad boy goes back to at least Shakespeare’s time, and much earlier, says the film scholar Timothy Shary. “There’s always something compelling about young men who are stuck between wanting to be cold paragons of adult machismo and needing to confront their innate emotional torments,” he says. The most iconic bad boys emerged in the 1950s via Marlon Brando as a biker gang leader and James Dean playing deadly chicken. Fast-forward and today he is embodied by the likes of Timothee Chalamet and Noah Centineo, who “play self-aware and sensitive characters” who resolve masculine conflicts “through getting in touch with their feelings more than acting out against the system,” says Shary.

The ’90s bad boy arrived in the midst of that arc from “rebel without a cause” to millennial self-reflection. He was tortured in part because of a sense of gendered evolution alongside enduring “conflicts with outdated expectations of masculinity, such as aggression, repression, and arrogance,” says Shary. “We started seeing roles like that in the ’90s through teen TV like 90210 and Dawson’s Creek, and with stars like Leonardo DiCaprio and Johnny Depp,” Shary explains. The early ’90s also saw the emergence of films like Boyz N the Hood and Juice, which featured Cuba Gooding Jr. and Omar Epps in tortured roles—and yet the Hollywood bad boys who received the Teen Beat treatment were decidedly white. Those vaunted white stars often faced melodramatic tortures, as opposed to the systemic problems of racism and class inequity.

The sense of conflict with outdated gendered expectations was just as present in the girls who lusted after the ’90s bad-boy heartthrob. He emerged during a “girl power” movement that brought privileged young women a sense of possibility—and disappointment. The social historian Carol Dyhouse, author of the upcoming Love Lives: From Cinderella to Frozen, argues that you can “understand the changing fashions in men by looking at women’s own social positions at any particular time.” In the ’90s, against the backdrop of girl power, “young women were being told that they were strong,” she said. “That meant that they were in a sense freed up to fancy the sensitive types because they’d been told they were powerful themselves.”

It isn’t that women hadn’t previously been attracted to such traits, says Dyhouse, but rather that greater independence made longing for a sensitive soul, as opposed to a “provider type,” somewhat more practical.

However, Dyhouse continues, “most ordinary women, they probably didn’t feel all that powerful,” she said. “There’s a kind of mismatch between the anxieties you feel as a young woman, as an adolescent, and what the world tells you is available.” Well, here came the sensitive bad boy with his relatable inner conflict and superior emotive powers. He wasn’t going to sweep you off your feet so much as understand your pain, feel your pain, and scream it to the heavens for you. As Shary puts it, “Girls certainly have more reason to feel tortured than boys, but they are often stuck within the double standard of appearing attractive to boys while seeking independent identities free of boys.”

The appeal of the bad boy hinges on power, says Dyhouse. “It plays on your sense of power and your sense of powerlessness, which probably sums up the predicament of young women in the 1990s,” she says. That period also saw the growth of the “girl delinquent” in films like Freeway and Foxfire, which center around young women going after murderous or sexually abusive men, and which “showcased a new generation of girls strategically using their pent-up irritations to redress their gender inequality,” as Shary put it in an academic paper. Of course, the bad boy archetype also taps into what Dyhouse calls the “age-old” idea of a woman being able to change a troubled man, a fantasy with its own undercurrents of power and control.

Bad boys are romanticized and heroized, but the “bad girl” is rarely exalted in the same way. For girls, lusting after “bad” is much safer than being bad. This aligns with the way in which women more broadly claim, or settle for, power and freedom attained through men—by pleasing them, by being desired by them, by being married to them. The psychologist Polly Young-Eisendrath wrote that, “lacking clear avenues for developing our power directly, [women] learn to be indirect in making emotional arrangements based on others needs and wants, and how we would like to be seen.” This adaptive contortion loosely applies to the sensitive bad boy, too: what a woman wants for herself is channeled into desire for the man who appears to have it.

I told Dyhouse about my teenage love for Leo wailing in Romeo + Juliet and she responded, “The image of the man screaming at the heavens like that, it draws on your compassion but also on your identification, doesn’t it?” she said. “You probably felt that screaming urge inside of you, and the fact that Leonardo DiCaprio could express it probably only cemented the love bond.” The sensitive ’90s bad boy could be both desire object and role model, heartthrob and avatar. “Half the time, our fantasies are our own projections,” says Dyhouse. “We fantasize about objects which on some level represent our own obsessions and needs. There’s never a clear line in desire between who you are and who you desire.”