The Demands of Positive Celebrity Coverage

Entertainment

It’s been a rough week to be a star, and a rough week to be someone who listens to what stars have to say. At least, that’s what social media tells me. Some of the most famous people making music today—Ariana Grande, Cardi B, and Justin Bieber (as well as Lizzo, a darling of critics and her fans but not quite of superstar status… yet?)—have shared their thoughts online regarding the state of media in 2019. None of it advocates for a free press, much less even contends with that notion. The gist is that journalism should be service journalism that primarily serves the powerful and their images.

If the stakes were more serious, if they actually posed a threat to the Constitution, you might say that these sentiments, at their broadest and least aware, were inching towards the fascistic. The actual situation is pretty ridiculous, and its potential outcome is not necessarily apocalyptic, but it’s worth noting that this wave of celebrities attacking the press and attempting to coerce it into “positive” coverage on their behalf comes during the presidency of a man who has relentlessly conflated criticism of him with lies, who has attacked outlets that investigate, question, and critique his performance and competence instead of journalistically fellating him.

We’re all sensitive people, and we have at our fingertips the availability to broadcast that sensitivity, whether by art or by its virtual opposite, the tweet.

Must be something in the air. As someone who gets paid to tell the truth, as best as I can muster it from my inherently fallible one-perspective human vessel, I’m galled by even the slightest attempt of a subject dictating coverage. And yet I think I understand to a certain degree why these celebrities seem so thin-skinned and intolerant of anything less than entirely credulous praise: The sensitivity that allows these people to express themselves in public also makes them vulnerable to whatever comes after. You can’t expect one channel without the other. The vast majority of us aren’t able to turn on and off emotions that easily. We’re all sensitive people, and we have at our fingertips the availability to broadcast that sensitivity, whether by art or by its virtual opposite (except in very select hands), the tweet.

But oh, do weeks like this make me wish there was another way, as I lie typing in the bed that hyper-connectivity has made. A trivial segment on E!’s Nightly Pop show, in which co-host Morgan Stewart did little more than point out Justin Bieber’s bad lip-syncing at Coachella (which was objectively and certifiably lax, in that he didn’t even bother to hold the microphone up to his face when he was supposedly singing at points), prompted a several-tweet read from Bieber:

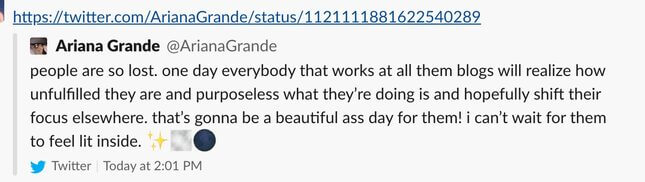

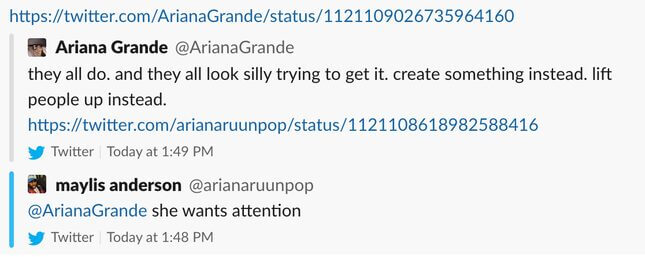

Ariana Grande, whose Coachella set Bieber occasionally sang to a backtrack in the middle of, jumped in with an even more exacting indictment of internet media in now-deleted tweets:

You know, if she were curing cancer or figuring out a way to make sucking the carbon dioxide out of our atmosphere and blasting it into space politically feasible, I might care more about Ariana Grande’s definition of purpose. But she’s making pop songs. Art is inevitable and necessary, but if she weren’t doing what she does, someone else would be in her place, and the world wouldn’t know the difference. For all but an infinitesimal number of people in all of existence, “purpose” is a rather subjective scale (Bieber album titles be damned). I’m sure Ariana Grande’s 152 million Instagram followers, though, suggest otherwise to her.

Cardi B, meanwhile, posted a multipart video rant on Instagram in the wake of the Shade Room’s coverage of her husband Offset’s recent charges. She took the popular Instagram/website to task for not posting more positive content. Well, it’s not called the Shine Room.

That she began this demand for positivity by referring to Shade Room proprietor Angelica Nwandu as a “water buffalo built bitch” tells you everything you need to know about turning to Cardi B for etiquette guidelines. And all the high-minded “should”-slinging doesn’t acknowledge that writerly sensibilities are not easily segregated. They bleed into each other like paints. The press needs the freedom to be “mean” in order to be true. It’s not that Cardi is dead wrong about the Shade Room’s bias or totally clueless about how press works (she explicitly acknowledges that not all coverage will be positive). It’s just that these arguments against speech start to feel mighty hypocritical when spat from the tongues of public speakers from their oversized platforms. The underlying sentiment boils down to: “Shut up and listen. I get to speak, not you.” Kanye West has repeatedly taken this stance, denouncing criticism of his work, both specifically—after Pitchfork posted its rave 9.0-rated review of The Life of Pablo, West tweeted: “Pitchfork, the album is a 30 out of 10…To Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, New York Times, and any other white publication. Please do not comment on black music anymore.”—and in the abstract. Before the release of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, which went on to be his most acclaimed album, West mused in an interview, “I’m offering so much more, the songs are 7-8 minutes long. How do you even send this in for reviews? Why would people even… review it?”Criticism just formalizes the unstoppable process of engagement. It does not refine or perfect it.

Sometimes it feels like nothing is ever enough. In 2017, Spin posted an exposé about the debacle that became the MTV News overhaul of 2015. One of the most alarming sections of the piece detailed how relationships between the network and artists interfered with objective journalistic coverage. Then-music editorial director Jessica Hopper told her staff that they might have to “nix” writing about DJ Khaled “unless it’s like, KHALED IS GREAT.” Additionally, a lukewarm review of a Chance the Rapper performance that focused on the ‘emotional disconnect’” writer David Turner felt listening to Chance’s Coloring Book album was deleted from the site after, according to a memo from Hopper, “Chance and his management became aware of [writer David Turner’s] piece via the repost on Snapchat Discover and subsequently told MTV, amid high level negotiations for linear specials, that he was never working with MTV again because of it.” When Spin reached out to Chance’s manager Pat Corcoran, he said that he and his client agreed the article was “offensive.”

Chance the Rapper, one of the most beloved and affirmed artists of his generation, allegedly could not handle the continued existence of a review that contained something less than effusive praise. Coloring Book’s current Metacritic score is 89, which according to the site indicates “universal acclaim.”

While seemingly irrational, it is not uncommon to be deflated by a few stray voices of negativity instead of remaining uplifted by a legion of listeners who think you’re the bees knees. Citing the work of Stanford professor Clifford Nass, a 2012 New York Times piece “Praise Is Fleeting, but Brickbats We Recall,” explained: “Negative emotions generally involve more thinking, and the information is processed more thoroughly than positive ones, he said. Thus, we tend to ruminate more about unpleasant events—and use stronger words to describe them—than happy ones.” Further, this focus on the bad may even have an evolutionary basis. “Those who are ‘more attuned to bad things would have been more likely to survive threats and, consequently, would have increased the probability of passing along their genes… Survival requires urgent attention to possible bad outcomes but less urgent with regard to good ones,” the article says, quoting a 2001 Review of General Psychology article called “Bad Is Stronger Than Good.”

Perhaps that helps explain the almost unfailingly upbeat Lizzo’s tweet that many suspected was a response to Pitchfork’s review of her new album, Cuz I Love You.

Rawiya Kameir’s write-up of the record was indeed withering (“Her pledge to be ‘ARETHA FRANKLIN FOR THE 2018 GENERATION’ is evident, if not quite actualized; this generation’s Natasha Bedingfield is maybe more accurate”), so much so that the 6.5 rating seemed charitable. Still, Lizzo could afford a pan—Cuz I Love You’s Metacritic score is currently 84.

But then she walked back the hardship-wishing to a workforce that is already often tossed pennies per word:

And then she really walked it back.

It was all so silly. Even if most people love a thing, some will not. The most brain-stimulating art is hardly the most popular, and in a world of increasingly splintered attention, being able to command enough eyes and ears to have what can be considered an audience at all is a real feat. What these anti-criticism arguments don’t acknowledge is that criticism is just a natural process writ public. People experience art, they form an opinion of that art, they share an opinion about it. Criticism just formalizes the unstoppable process of engagement. It does not refine or perfect it; it is often written by people who are out of their depth (both in terms of knowledge and expression), but it is nonetheless as inevitable as art itself. Again, both channels must be open for either to work. The result can be a contentious relationship between creator and consumer, between subject and journalist. This may result in disagreements and awkwardness, but it is much preferable to allowing anyone with a following to become a mini dictator.

Celeb reactions to the reactions are as natural as the reactions themselves, though, and I suspect this contentious relationship to feedback has always existed, it’s just that now everyone has an easy way of sharing each and every thought that scurries around their head (and would otherwise end up belly-up sooner than later). It feels like celebrities are just now ramping up their attacks on speech, but I think celebrities are just being celebrities as they always have been. Joni Mitchell complained for years that Rolling Stone named her 1975 album The Hissing of Summer Lawns the worst of that year until, oops, she realized the magazine had said it was the worst album title of that year (the magazine was still wrong in a year that delivered Physical Graffiti, Come Taste the Band, and Extra Texture (Read All About It)).

That Joni Mitchell, a bona fide legend who’s as prototypically singer-songwriter as they come, should have anything to complain about regarding the public’s reception of her work seems absurd on its face. But then again, Mitchell never won Album of the Year at the Grammys—an album of covers of her work by Herbie Hancock, however, did. Her suspicions of under-appreciation aren’t exactly right, but they aren’t exactly wrong either. The truth is complicated.

To some degree, most of us have played a role in constructing this contentious atmosphere in our midst that holds a lot of colliding opinions bouncing around, hoping to make the loudest mark. It’s at least purgatory—there’s little progress and little indication of what progress might even look like in the realm of petty, fame-based affairs—but it’s totally understandable when it feels like hell. At least we’re all in it together.

Correction: A previous version of this post stated that David Turner’s deleted piece originally on MTV News was an album review. It was a concert review that contained commentary on Chance the Rapper’s album, as well. The post above has been changed to reflect the distinction.